For many years for the Turkish audience Yol (The Road) was the greatest Turkish movie which no one had ever seen. As a teenager with cinematic interests, growing up in Istanbul in the 90s, I used to wonder what so special about this movie was, that would make it so different from hundreds of others I had seen. A stereotypical 80s Yesilcam drama (Turkey’s Hollywood) would not have any chance to win Palme D’Or, let alone could ever receive such critical acclaim. I had first seen Yilmaz Guney in such Yesilcam melodramas, which he had starred in. But then I already knew him as an icon for the left-wing movement and Turkish cinema. Yol and its success in Cannes was certainly the highlight of his career and probably of his life that has made him a national legend but it was certainly not the only reason behind it. He had already given signs of a genuine cinematic insight for life in Turkey with his Umut (Hope, 1970). His closeness with political activists despite his star status in Yesilcam was unheard of and much admired by the left-wing youth groups.

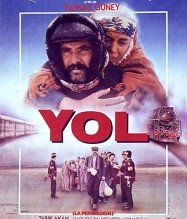

Yet, without Yol, it would possibly be easier to falsely attribute his legend status more to his political activism than his achievements in film. Yol was made despite numerous obstacles laid infront of its makers at a time right after the bloodiest coup d’etat in Turkey. Shot while Guney was in prison, based on his script and detailed directing instructions, it features Tarik Akan, another Yesilcam star who took the risk of imprisonment by being a part of the cast. Yol embodies Guney’s love for this land and its people. However, he does not hold off from pointing out the common prejudices, backwardness and weight of feodal traditions. Perhaps he deliberately leads our sympathies towards this bunch of outsiders whose ties to the values of the outside are either loosened or already broken, rather than the “innocent” that dwell beyond the prison walls.

Through the stories of these five men, told in parallel, Guney and Goren creates a panorama of Turkey. Guney here manages to keep all stories intriguing and the movie in balance with his realistic and sincere script and his crisp editing. He is ahead of his European or American contemporaries in using parallel storylines to depict a situation, a period, rather than substories of a common plot. Other remarkable examples of such storytelling in the West arrives many years later, Pulp Fiction (1994), Bure Baruta (Cabaret Balkan, 1998), Magnolia (1999), Amores Perros (2000).

The dark humour embedded in his script essentially loaded with sorrow is rare a thing among his Turkish contemporaries. He neither looks down at his characters nor exaggerates to make things grotesque, his gaze is distant enough to let us swing back and forth, between sad and funny.

Yol marks the beginning of Guney’s ephemeral golden era and shines as the highlight of his cinema. It may not be a landmark in the world cinema but it sure is for Turkish film history. From Demirkubuz to Ceylan, many contemporary Turkish filmmakers cite him as a major inspiration. I believe Yol remains relevant for anyone who aspires to be a filmmaker telling the stories of these lands, like a bedside book or a language guide.